The Specification Shift: You're Not Undisciplined, You're Underspecified

Make knowledge work for you next week: why saving feels like learning, why scaffolding beats the model, the Zettelkasten failure pattern, AI agent security, full-life delegation, and skills as systems

This week’s curation: official releases and app updates, practitioner discussions, long-form from newsletters and podcasts, plus the prompts, templates, and scripts people are actually shipping (and you can use today). I’m always looking for two things: the “why” behind the “what,” and practical things I can implement to turn information into action.

Here’s something I’ve noticed.

The people who’ve stopped tool-hopping, who actually use their notes, who’ve built AI workflows that feel effortless… don’t talk about discipline. They don’t talk about consistency. They don’t even talk about finding the right system.

They talk about clarity. Not the inspirational kind. The mechanical kind: specifying what they want in enough detail that a system (or an agent) can do it without follow-up questions..

Let me show you what that looks like.

1. Saving Gives You Dopamine, Not Value

A confession Reddit post hit 150 upvotes: “I’ve been saving articles and resources for years, but I never actually use them.”

847 articles. Untouched.

I checked my Raindrop while writing this. Thousands of links and the oldest saved in 2021. I felt called out. One commenter put it plainly:

“The act of saving something gives me a little dopamine hit like I accomplished something. But I never actually DO anything with it.”

The comments revealed the mechanism: the reward comes from capturing, not using. The save button delivers a small dopamine hit (”future me will appreciate this”) and that hit is the actual goal. The article itself is irrelevant.

💎 Saving new information feels like learning. It’s not.

This reframes the problem entirely. You’re not failing to use your saved items. You’re succeeding at something else: the collection ritual.

The intervention that works: forced reflection before the click. One commenter requires themselves to write one sentence about why they’re saving something. Not a summary, but a reason. “Because I might need it for...” forces the question of whether you actually will.

Most items don’t survive that question.

The insight isn’t about self-control. It’s about noticing your brain’s incentives and building a tiny constraint that breaks the loop.

Try it:

Quick (30 sec - 5 min): Before your next save, complete: “The action I’ll take is ___.” No answer? Don’t save.

Deeper (15 min - 1 h): Open your read-later app. Audit 20 random saves with the same question. Delete what fails. Notice how many survive.

This week: Save Monday-Thursday only. Block Friday afternoon to process. The constraint that actually beats guilt.

Source: 847 saved articles confession

2. The Model Isn’t the Magic. Your Scaffolding Is.

Twenty-five years ago, the Matrix called the bad guys “agents.” Recently, that joke went viral (14,000 likes, half a million views) because we’re all building agents now.

But here’s what the meme misses: agents aren’t the enemy. The real villain is building them without understanding what you’re building and why.

Daniel Miessler just rewrote his Personal AI Infrastructure guide from scratch. Buried in the 7-component architecture is a line that stopped me:

”The model matters, but scaffolding matters more.”

We’re all obsessing over GPT-5 vs. Claude Opus vs. Gemini Ultra. But Miessler, who’s been building AI systems longer than most, says the model is just one piece. The real intelligence comes from what wraps it:

the context it has about you

the skills you’ve encoded

the tools it can use

the security boundaries

how agents coordinate

how the interface feels day-to-day.

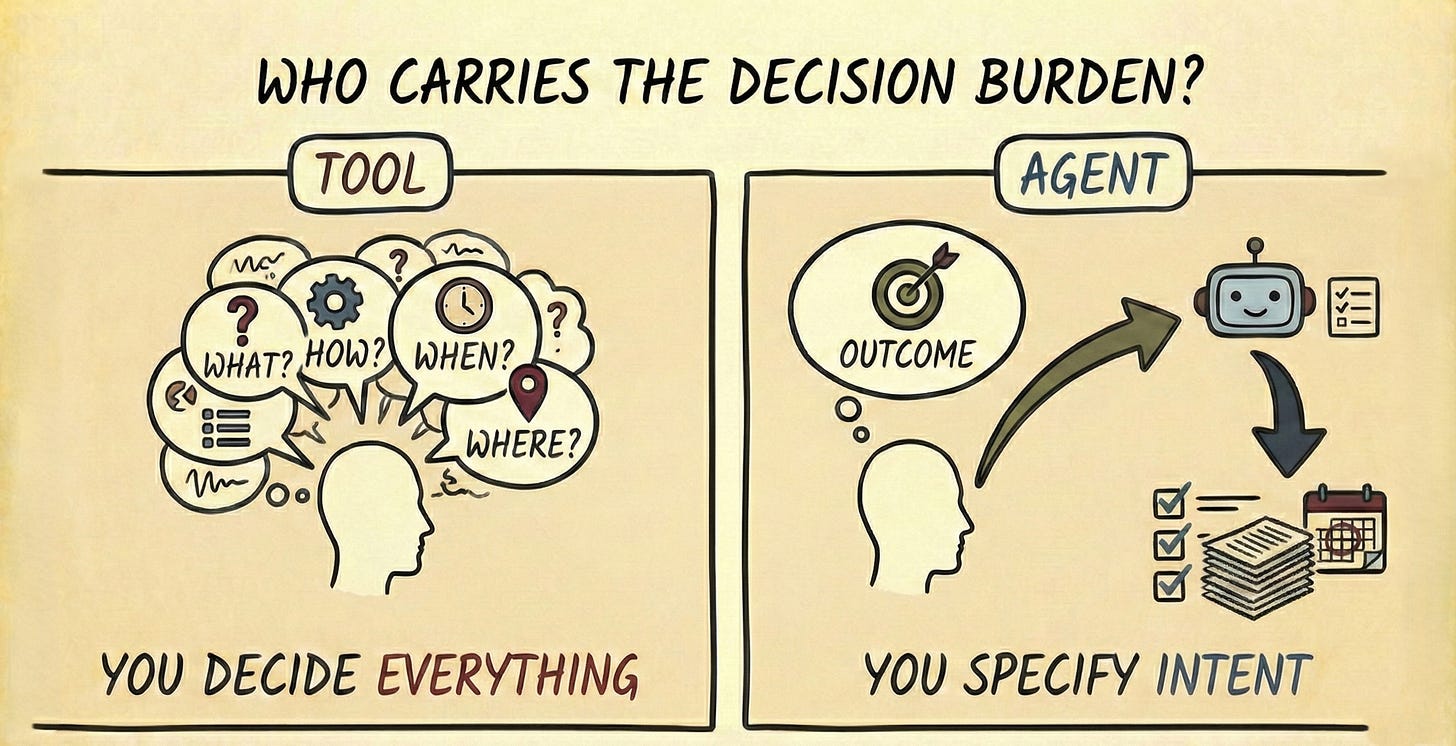

The real question isn’t AI tools vs. AI agents. It’s: who carries the decision burden?

Tools require you to decide what to do, then execute. Agents require you to specify intent, then delegate judgment. This is why the agent shift matters more than any individual capability bump. Agents aren’t smarter. They absorb the micro-decisions that quietly drain you.

An important distinction: Agents solve input (what comes to you). They don’t solve processing (what you do with it). Automating delivery doesn’t fix the 847-article backlog. It might make it worse. Automation and constraints are opposite strategies for different problems. Use both, but don’t confuse them.

Try it:

Quick (30 sec - 5 min): Open your AI tool. Ask: “What do you know about me?” The answer reveals your scaffolding gaps.

Deeper (15 min - 1 h): Audit your intelligence stack. List: (1) context it has about you, (2) skills you’ve encoded, (3) access you’ve granted. Default setup = running a Ferrari on bicycle wheels.

This week: After every AI correction, say: “Remember this fix for next time.” Watch your scaffolding build itself..

Source: Building a Personal AI Infrastructure

3. Your Note-Taking System Isn’t Failing Because You Lack Discipline

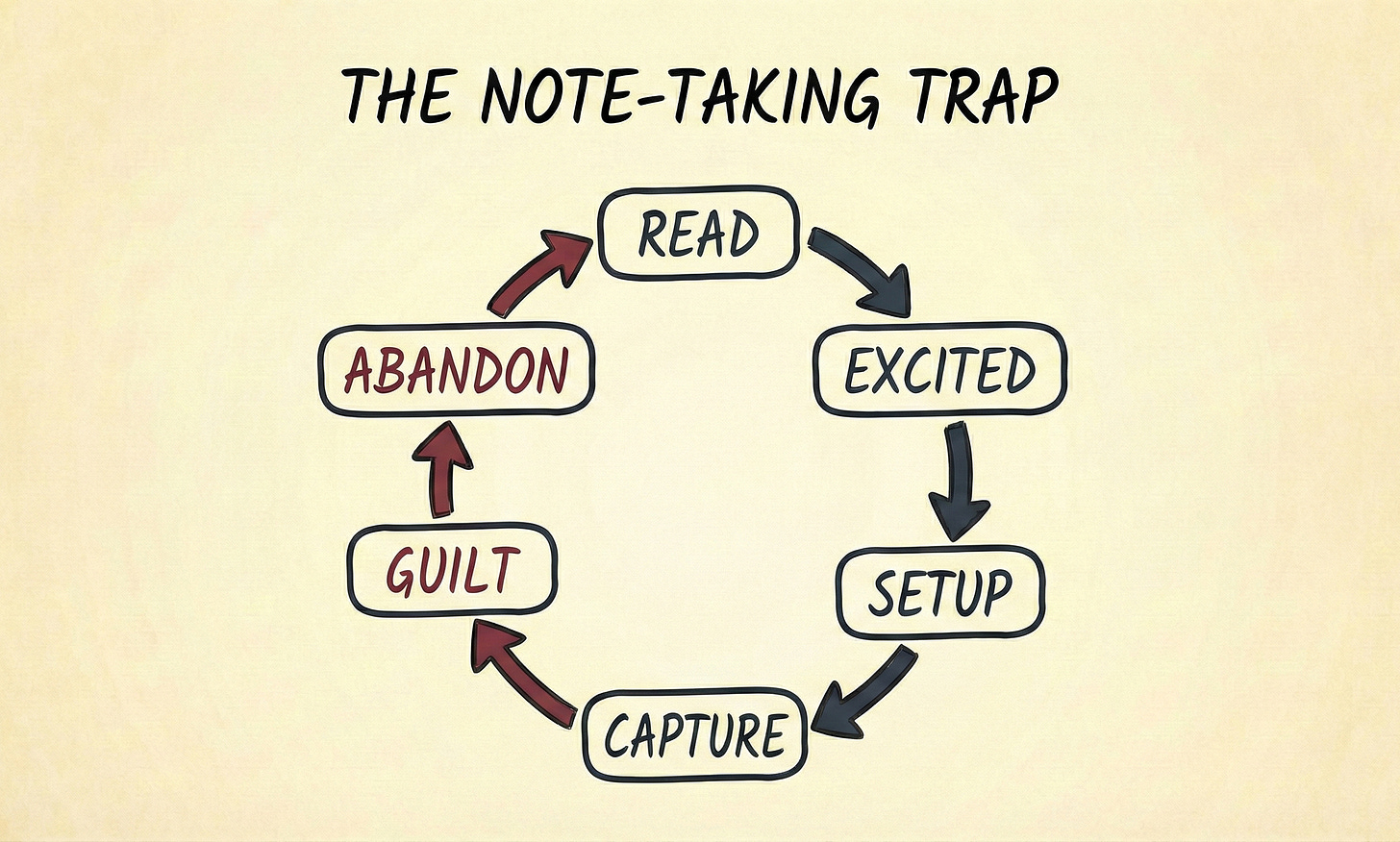

Someone posted on r/Zettelkasten: “I’m researching why Zettelkasten fails for a lot of people.”

The responses revealed the same pattern, and it applies to any knowledge management system, not just Zettelkasten:

Read → Excited → Setup → Capture → Guilt → Abandon

The common interpretation: “I’m not consistent enough.” The actual cause: decision overload.

Every note demands micro-judgments: Where does this go? How do I tag it? Should I link it? What’s the atomic idea? Is this worth keeping?

That’s a design problem, not a discipline problem.

Most failure stories boil down to infinite flexibility. The system asks “how do you want to organize?” and you freeze. Most success stories add constraints:

just markdown files

processing on Fridays

“name the action before saving”

fewer folders, fewer choices, fewer modes

The system requires you to make dozens of judgment calls per session. Each call costs willpower. Eventually you stop.

I’ve lived this cycle three times. Evernote, then Notion, then Obsidian. The third time worked, but only because I stopped trying to organize and connect everything and started adding constraints.

Here’s the thing: the people who make their systems work aren’t more disciplined. They’ve either automated the decisions or have enough domain expertise that the “where does this go?” question answers itself.

For everyone else, the guilt isn’t a signal to try harder. It’s a signal that the architecture doesn’t fit.

This is Miessler’s scaffolding principle in action: if your system demands constant micro-decisions, you’re fighting willpower instead of building infrastructure.

Try it:

Quick (30 sec - 5 min): Count your notes from last week. Capturing vs. processing: what’s the ratio? If it’s 4:1, you’re building debt.

Deeper (15 min - 1 h): List every decision your note-taking system asks you to make. For each: can you automate it, constrain it, or eliminate it?

This week: Cut your capture rate in half. Process what you have before adding more.

Source: Why Zettelkasten fails

4. Your AI Agent Needs a Security Model (Not Just a Password)

OpenClaw is the hot new AI agent everyone’s talking about. 1Password’s Jason Meller tried it. His verdict: “Incredible. Terrifying.”

The problem isn’t capability. OpenClaw can build kanban boards, make reservations, plan its own database migrations. The problem is that all your credentials, API tokens, and everything the agent remembers about you sits in plain text on disk.

One infostealer. That’s all it takes.

An attacker who grabs your memory files and API tokens can impersonate you, phish your contacts, or (in Meller’s words) “blackmail you with your own thoughts.”

But here’s where it gets interesting. Meller doesn’t say “don’t use AI agents.” He proposes treating them like new hires:

give them their own identity, not your personal credentials

grant minimum authority at runtime, not everything upfront

use time-bound, revocable access, not permanent keys

This connects directly to Miessler’s PAI framework. Security isn’t a feature you bolt on. It’s the fifth of seven architectural components. Without it, your “second brain” becomes a liability.

The specification shift applies here too: if you can’t specify what access your agent needs, you’ll either give it too much (risky) or too little (useless).

Try it:

Quick (30 sec - 5 min): List the directories your AI can access. Can you name them all? Most people can’t.

Deeper (15 min - 1 h): Do a “new hire” review. Open your AI’s settings and ask: “Would I give a new employee this much access on day one?” Revoke what fails.

This week: Add one security hook: a notification when your AI accesses sensitive files. One is better than none.

Source: It’s incredible. It’s terrifying. It’s OpenClaw.

5. Full Life Delegation Is Already Happening

Andrew Wilkinson runs a holding company. Here’s what Claude Opus now handles for him: email triage (not just sorting, but deciding what matters), relationship advice (”my AI therapist,” he calls it), personal styling from wardrobe photos, and investment analysis across portfolio companies.

This isn’t a productivity experiment. It’s his actual workflow.

The pattern: Wilkinson doesn’t use AI to do tasks faster. He uses it to avoid making decisions he’d rather not make. The AI carries judgment that used to live in his head.

The honest caveat: he has resources most of us don’t. Time to experiment, tolerance for failure, existing systems to delegate from. But the architecture is replicable. The question is what decisions you would delegate if you could.

If you can’t articulate what those decisions are, you’re not ready for agents. Specification comes first.

Try it:

Quick (30 sec - 5 min): Write down three repeated decisions you resent making. That’s your delegation list.

Deeper (15 min - 1 h): Pick one decision from your list. Spec it out: What info does the AI need? What output format? What constraints? What’s a failure mode?

This week: Track “decision fatigue” for 3 days. Every time you feel that tiny internal groan - log it. That’s the work to delegate..

Source: Opus 4.5 Changed How Andrew Wilkinson Works

6. Skills Are Systems, Not Prompts

Boris Cherny (Claude Code) recently shared how the team uses it, and the meta-pattern matters more than any individual tip:

They don’t treat Claude as a chat interface.

They treat it as a system they continuously program.

His team’s rules:

“If you do something more than once a day, turn it into a skill.” They’ve built skills for syncing 7 days of Slack, Google Drive, Asana, and GitHub into one context dump.

“After every correction, say: ‘Update your CLAUDE.md so you don’t make that mistake again.’” Claude is eerily good at writing rules for itself. Ruthlessly edit your CLAUDE.md over time.

“Start every complex task in plan mode.” One team member has Claude write the plan, then spins up a second Claude to review it as a staff engineer. Don’t push through. Re-plan.

“Pour energy into the plan so Claude can 1-shot the implementation.” The investment is in definition, not execution.

Every hour spent specifying a skill saves ten hours of re-explaining. This is what Miessler means by “scaffolding matters more than the model.”

I’ve started doing the CLAUDE.md correction thing. There’s something satisfying about watching Claude write better rules for itself than I would have thought to write.

Try it:

Quick (30 sec - 5 min): After your next AI correction, say: “Update your rules so you don’t make that mistake again.”.

Deeper (15 min - 1 h): Identify one thing you do more than once a day. Write a “skill spec”: context, constraints, output format. Save it where your AI can access it.

This week: Every time you re-explain something to your AI, ask yourself: “Could this be a skill?” Build one.

Sources: Thread by @bcherny

The Shift

The six sources point in the same direction:

1. Hoarding persists because collecting bypasses actual use

2. Intelligence comes from scaffolding, not just the model

3. Systems fail because they demand too many decisions

4. Security requires upfront specification of access

5. Full delegation is possible when you can specify what you want

6. Skills work when the decisions are made upfront

💎 The bottleneck moved from execution to specification. The winners aren’t “more disciplined.” They’re better at definition: what they want, what matters, what access is necessary, what decisions they refuse to keep paying for.

—Elle

P.S. We can’t practice having more willpower, but here’s what I find hopeful: specification is learnable in a way that daily discipline isn’t. We can get better at naming the action, defining the output, bounding access, and making decisions once - then reusing them as systems. That skill compounds in a way discipline rarely does.