💎 Notes That Ship: Knowledge Organization for Creators & Makers.

What Kind of Knowledge Garden Are You Growing? There are distinct styles, and you can identify yours. Part 2 of the Knowledge Organization Styles Series.

In the last edition, we explored the Networkers - people who build knowledge like constellations, connecting ideas across domains through Zettelkasten, Wiki, and Hub & Spoke structures.

But not everyone thinks in webs. Some people think in projects. They don’t take notes “just in case.” They take notes because they’re building something right now and need to capture decisions, document iterations, or create reference material for this specific thing.

Welcome to Part 2, dedicated to the Creators & Makers — the people who treat their notes not as a library, but as a factory floor.

The Four Knowledge Organization Styles

New here? Here’s the quick version:

After analyzing 100+ public digital gardens for their structure and navigation patterns, I landed on four dominant styles of personal knowledge organization::

The Networkers build webs of connected ideas.

The Makers structure everything around output.

The Chronologicals let time do the filing.

The Curators collect and organize external resources.

The four styles aren’t personality types—they’re structural patterns that serve different kinds of knowledge work. Most people lean toward one primary style with a secondary influence. The goal isn’t to pick a perfect label, but to notice which pattern your best work naturally gravitates toward.

Today: The Creators & Makers.

This edition is for the Creators & Makers: people who think in projects, versions, and shipped work. If your main question is “What did I actually make this month?”, your notes should behave more like a lab, a living book, or a public studio than a library or inbox.

If you often feel paralyzed by complex tagging systems, or if you feel guilty that your “graph view” isn’t pretty enough, you might simply be using the wrong tool for your job. You don’t need a map; you need a workbench.

This edition focuses exclusively on The Makers and the Output-Heavy structures designed for those who learn by doing.

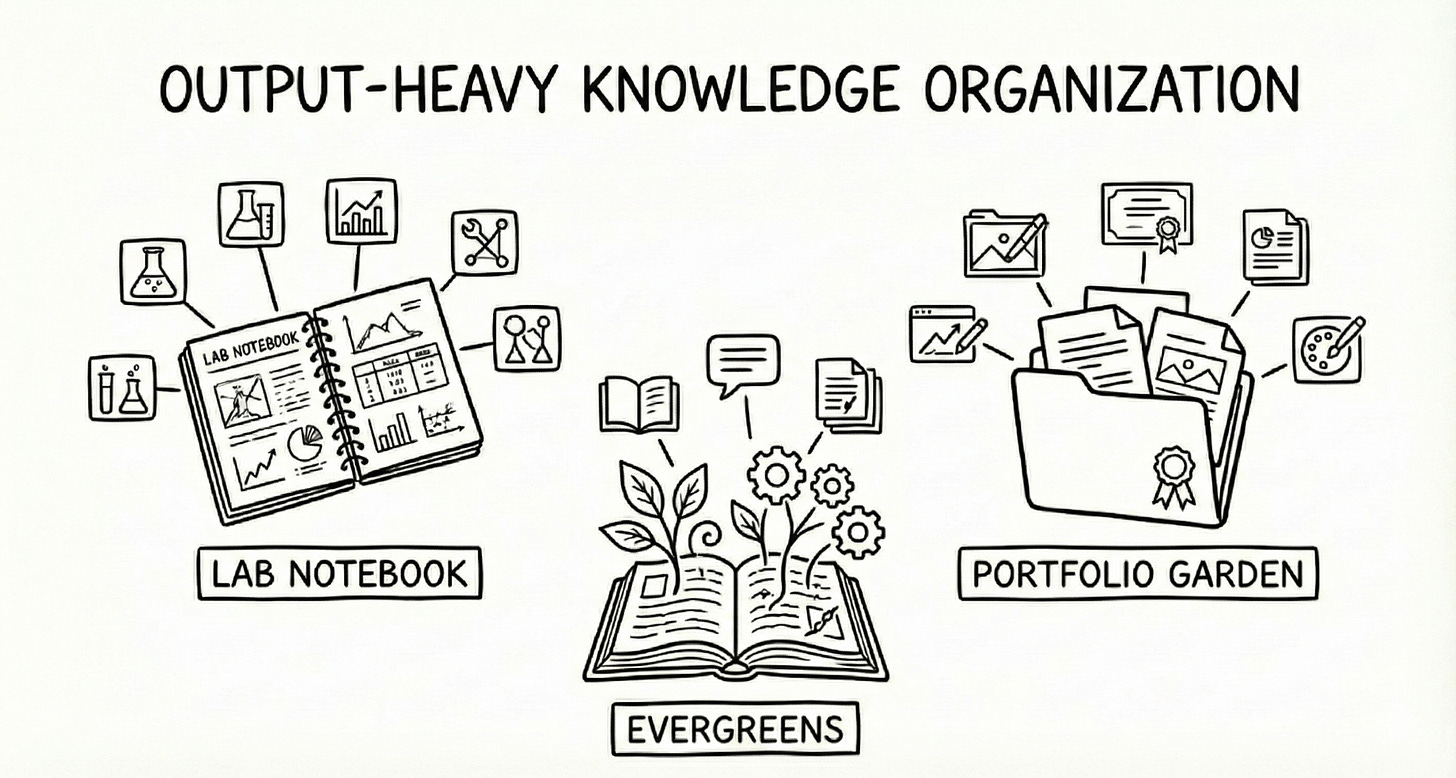

Lab notebooks catch the messy middle; Evergreens capture the enduring ideas; Portfolio gardens tell the public story.

🧪 Lab Notebook / Changelog

A “working out loud” space for unfinished experiments and messy thoughts in progress. Unlike a polished portfolio piece, the Lab Notebook focuses on documenting the evolution of work rather than just the final result. It’s a place for comments, code snippets, failure logs, and iterative testing

Key Traits:

Work-in-progress documentation: unfinished thoughts, rough experiments, decision rationale.

Process transparency: the “why” behind choices, not just the “what”.

Failure-friendly mindset: dead ends and pivots are features, not bugs.

The Vibe: Raw, iterative, “show your work.”

Used For:

Overcoming perfectionism: lowering the bar for publishing by embracing the “work in progress” state.

Debugging context: creating a paper trail to help your future self understand why a decision was made or how a result was achieved.

Showing your work: demonstrating process, competence, and tenacity to potential collaborators or employers—not just a shiny final object.

Examples:

→ Fabien Benetou’s Explorations — VR prototyping with detailed project logs.

→ Jacky Zhao’s Garden — Experiments with networked thoughts and technology.

Best Practices:

Write the why while it’s still obvious. The decision that feels self-explanatory today will be mysterious in six months. Date everything, link to the artifact (commit, file, draft), and don’t polish—the mess is the point. A changelog entry written in 2 minutes beats a retrospective you’ll never write.

Lower your standards. Lab notebooks only work if you actually use them, which means they can’t require effort. Skip the formatting, skip the complete sentences, skip the context-setting. Just answer three questions after each work session: What did I try? What happened? What’s next? Date it, tag it with the project name, and move on. The value isn’t in any single entry—it’s in the searchable trail you’re leaving for yourself.

Write as if you’re explaining it to “future you plus a mildly confused collaborator”: short, clear sentences, and a one‑line “next step” whenever possible.

More about Lab Notebooks:

How I Use CLOGs to Organize My Writing Files by Bob Doto — CLOGs (Chronological Logs) as a lightweight alternative to complex note systems.

💎 The changelog entry you write in 2 minutes is worth more than the retrospective you’ll never start.

🌲 Evergreens/Living Essays

Long-form, polished content designed to evolve over time. Unlike blog posts (which are snapshots), evergreens are updated, refined, and expanded as your understanding deepens. They’re ideas you expect to revisit for years, not weeks.

Key Traits:

Timelessness: concept-oriented rather than time-oriented (”How Gravity Works” vs. “My thoughts on gravity today”).

Publication-ready quality, but never “finished”: revision history often visible.

Subject mastery: deep exploration of specific domains or concepts.

Designed to compound: each revision makes the piece more useful, not just more current.

The Vibe: Authoritative, but calm and evolving.

Used For:

Building long-term intellectual capital on topics central to your work or thinking.

Creating reference material you’ll link to repeatedly: from other notes, social posts, and conversations.

Using writing as a tool to develop understanding, not just record it.

Establishing expertise publicly: Evergreens become the thing people cite when they reference your ideas.

Thinking through complex topics that can’t be captured in a single writing session.

Examples:

→ Gwern’s Essays — The gold standard for living, evolving and deeply-researched essays on AI, psychology, and statistics. Many pieces span years of revisions.

→ Maggie Appleton’s Garden — Beautifully illustrated essays; a “living book” on digital tools and anthropology.

→ Andy Matuschak’s Evergreen Notes — The origin of the concept. Atomic, densely linked notes written to develop ideas across time and projects.

Best Practices:

Don’t wait for perfection to publish. Gwern’s essays carry visible revision histories; Maggie Appleton uses “seedling → budding → evergreen” stages. The evolution is the point.

Form follows function. An evergreen can be a 10,000-word essay or a tight atomic note; what matters is that it’s written to compound, not to be consumed once and forgotten.

Link liberally. Evergreens gain power when they connect to each other. A web of interlinked essays becomes more than the sum of its parts.

More about Evergreens:

Evergreen note-writing as a fundamental unit of knowledge work — Why this approach changes how you think.

LessWrong Sequences — Essays designed to be read in order; another “living book” format.

💎 Blog posts age. Evergreens compound. The difference is whether you’re writing for this week or this decade

📂 Portfolio Garden & Building in Public

A Portfolio Garden is a hybrid between a digital garden and a creative portfolio. Finished work and live projects take center stage, but they’re surrounded by the background notes, experiments, and reflections that built them. It’s a “show your work” space: part showcase, part workshop. Unlike a traditional portfolio (which displays polished outcomes only), a portfolio garden shows what you’re trying, what’s working, and what you’re learning—in real time.

Key Traits

Professional presentation with personal texture: Projects, case studies, and artifacts are easy to browse and understand.

Notes as supporting documentation: Behind-the-scenes notes, diagrams, and process entries are linked from each project, not hidden in a private vault.

Creative demonstration: Skills and capabilities are shown through real decisions, constraints, and trade-offs—not just glossy screenshots.

The Vibe: Confident, generous, “here’s what I made and how I made it.”

Used For

Validating ideas early by sharing work-in-progress publicly.

Building trust with potential collaborators, clients, or employers who want to see how you think, not just what you’ve shipped.

Staying top-of-mind in your field—consistent sharing compounds into visibility.

Getting feedback that improves your work before it’s done.

Creating serendipity: public work attracts unexpected opportunities and connections.

Examples

→ Michael Karpeles’ Notebook — A blend of finished software projects supported by deep, Wikipedia-style research notes.

→ Robin Spielmann’s Garden — Design work showcased with supporting notes and process documentation.

→ Simon Hoiberg — A perfect example of Building in Public, documenting the journey of bootstrapping SaaS products from zero to revenue.

Best Practices

Story beats stats. Your process, pivots, and lessons learned are more relatable than polished case studies. Most people won’t buy your product, but everyone connects with a good struggle-to-solution narrative.

Share from where you are, not where you wish you were. “Expert advice” often fails because experts forget what it’s like to be a beginner. Progress updates from someone two steps ahead are more useful than wisdom from someone twenty steps ahead.

Connect your projects. A portfolio garden isn’t just a list of case studies - it’s a web. Link between projects, reference past work, and show how ideas evolved across multiple efforts.

Expect silence and do it anyway. Building in public requires vulnerability, and most people won’t take the risk. That scarcity is exactly why it works—the few who do it consistently stand out.

More about Portfolio Gardens & Building in Public

🕮 Show Your Work! by Austin Kleon — The foundational text: everyone has something valuable to share, and sharing it creates opportunities.

How to Build in Public 2025 — Comprehensive breakdown of the strategy and its benefits.

💎 Building in public is free, effective, and rare—because it requires the one thing most people won’t risk: being seen before they’re ready.

Try It Now

(60s) – Spot your current “system.”

Look at your last three completed projects. Where does the documentation live—chat logs? Commit messages? Nowhere? That’s your current system, whether you designed it or not.

(5 min) – Write one real changelog entry.

Pick one recent project decision you struggled with (pivot, tool choice, scope cut). In 3–5 sentences, answer: What did I decide? Why? What were the alternatives? That’s a lab‑notebook‑quality entry.

(15 min) – Choose your Maker entry point.

Need memory? → Start a Lab Notebook. After your next work session, answer: What did I try? What happened? What’s next?

Need to develop your thinking? → Start an Evergreen. Pick one idea you keep returning to. Write a rough first draft and commit to revisiting it monthly.

Need visibility? → Start a Portfolio Garden. Take one finished project and write the “behind the scenes” story: problem → approach → result.

👉 You’re Probably a Maker If:

You feel a note is “pointless” unless it connects to something you’re building.

Your best documentation happens during a project—and evaporates the moment you ship.

You’d rather have a messy desk and a finished product than a pristine system and a blank page.

You’ve said “I should really write that up” about a dozen projects—and written up zero.

If three or more hit home, your notes ask to be organized around output.

Parting Words

Makers don’t need more clever tagging. They need lighter scaffolding around the work they’re already doing.

Most productivity advice treats note-taking as an end in itself. Makers know better. Notes are scaffolding, not architecture—they exist to support what you’re building.

You don’t need a perfect system. You need a good enough system you’ll actually use. Pick one style. Start this week. Let the system grow from the work, not the other way around.

💎 The work you’ve already done is an asset. The question is whether anyone can find it - including the future you.

—Elle

P.S. Which Maker style resonated most? Hit reply and tell me: what’s one project you wish you’d documented better?